I don't mean to be facetious in choosing a LedZep(/Memphis Minnie) title for a post written in the midst of the current catastrophe in New Orleans, but let's face it: songs provide a soundtrack for just about every facet of human experience, somber as well as ecstatic.

Ever since I got off the phone yesterday with my friend Donna (pictured in this blog entry from just last month) who's still down there, I've been glued to the TV (I generally hate almost all TV coverage of global events these days) and far more informative websites like this one trying to get a coherent picture of what's going on down there. (BTW, my family lives on the other side of the state and in East Texas, and they're all high and dry. But I have at least a dozen or more friends in the affected area, and other than Donna I don't know what's up with any of them at all, since communication is pretty much impossible at the moment, and I imagine they all have their hands full with mere survival.)

There's nothing I can say in a music-related blog like this, written from the comfort and safety of my air conditioned, fully powered, dry little home thousands of miles away, that will shed any light on the situation or help anyone out. (Well, I guess I could put in the obligatory link to the Red Cross site, but surely you don't need me to suggest that.)

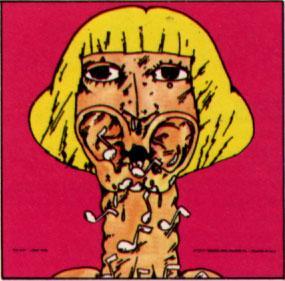

I just wanted to report that my initial musical impulse--one I still haven't acted on, because I fear it will just be too sad--is to listen to Randy Newman's great song "Louisiana 1927" from his immaculate Louisiana-centric 1974 album Good Old Boys (complete lyrics here).

The song is a sober, matter-of-fact account of the great nameless flood which nearly decimated Louisiana in the late twenties, back before we adopted the quaint, almost primitive habit of attributing human monikers and personalities to storms. The lyrics are disturbingly close to what's going on this very minute ("six feet of water in the streets..."), culminating in the chorus, "They're trying to wash us away." I think about that song any time my home state is inundated with water, which happens pretty often. The current devastation may be unprecedented, but it does exist within a historical context. (It's also not particularly shocking, I must remind folks; everybody knew this was going to happen sooner or later. That doesn't make it any less awful, of course, but it would be silly to suggest that the Big One took anyone by surprise.)

While I'm at it, allow me to put in a plug for Newman's entire album, which I'd say is his masterpiece. I first heard it almost by accident around the time it came out, pre-"Short People," and from the opening song "Rednecks" to the very end it struck me as one of the richest portrayals of Louisiana life I'd ever experienced. Still does. And it has nothing to do with southern belles or ragin' cajuns or Streetcars Named Desire or any of those other stereotypes of the state: just a collection of eccentric characters from the late 1920s through the 1970s (a period bracketed by two economic depressions) struggling to make a place for themselves in the world.

Speaking of songs and storms, my friend Scott (a one-time resident of N.O.) turned to the city's resident Queen of Soul, Irma Thomas, for "It's Raining," a lovely sad song whose raindrops weren't originally intended to be taken so literally. And according to this poignant but positive valentine to the cultural legacy and resilience of the Crescent City in the Washington Post, a piano player at the Royal Sonesta Hotel has been serenading stranded guests with "Stormy Weather." Maybe "I Will Survive" would be a wise choice, too.

What about you? Any songs for the storms of life? Good tunes for bad times?